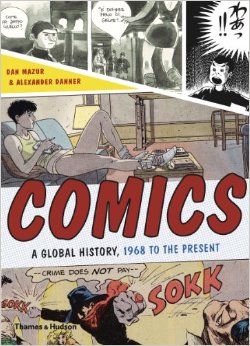

Upcoming in June from publisher Thames and Hudson, “Comics: a Global History, 1968-present,” written by Alexander Danner and me. Â I want to post some snippets from the book, including some great comics images (from foreign lands and bygone days) that we couldn’t quite fit in the book. Â

Upcoming in June from publisher Thames and Hudson, “Comics: a Global History, 1968-present,” written by Alexander Danner and me. Â I want to post some snippets from the book, including some great comics images (from foreign lands and bygone days) that we couldn’t quite fit in the book. Â

As the title suggests, the book covers the period from, roughly, 1968 until 2010. The introduction, though, provides some background on the development of comics around the world (focusing mainly on Europe, Japan and the U.S.) during the post-war era through the mid-60s.

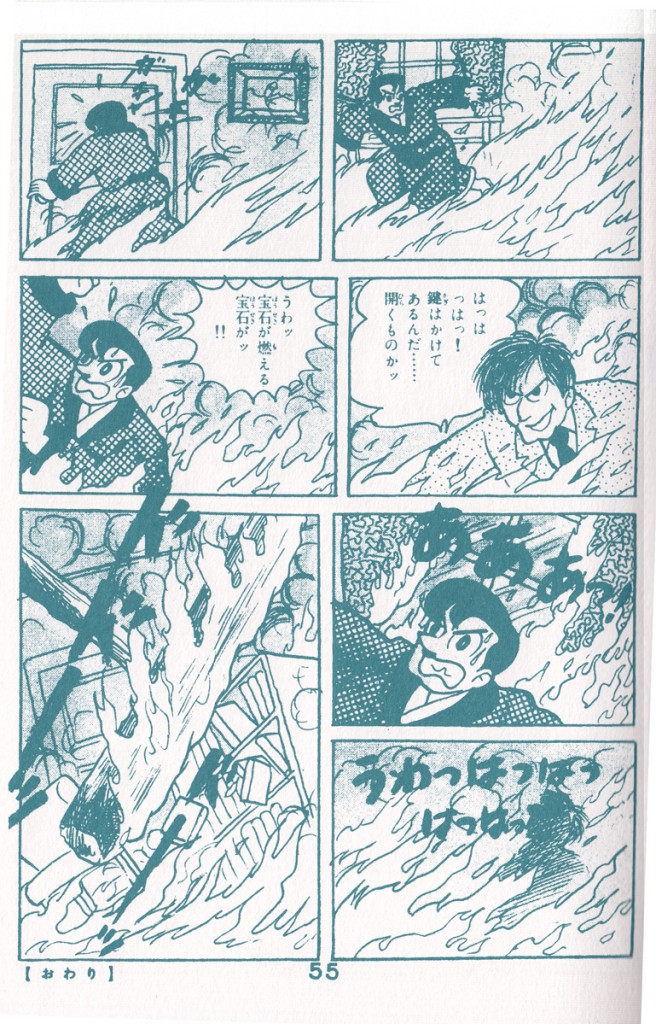

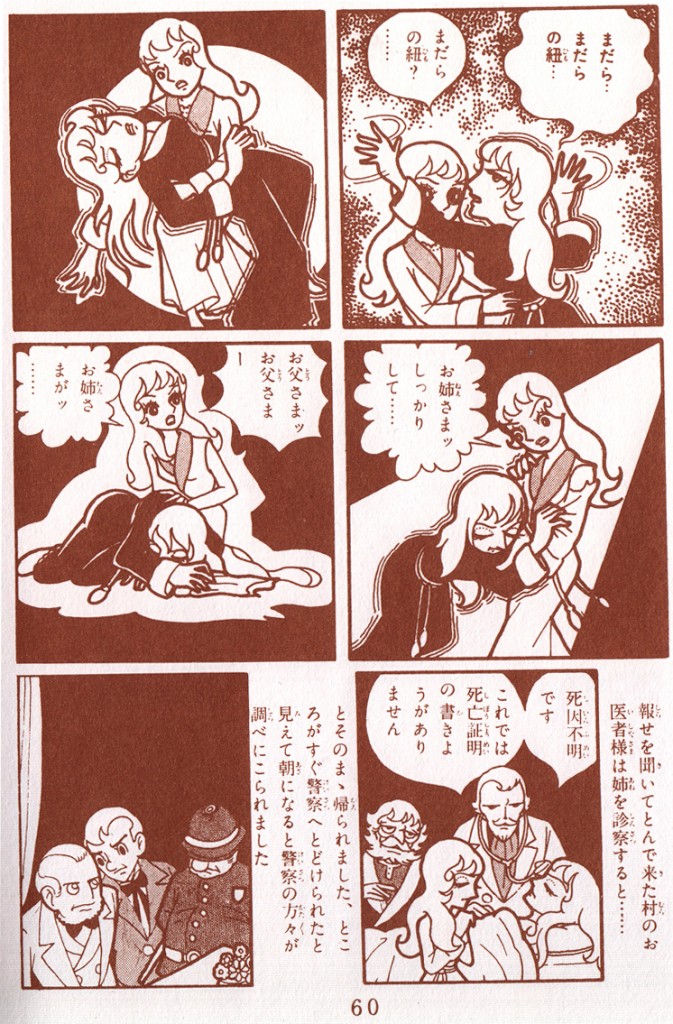

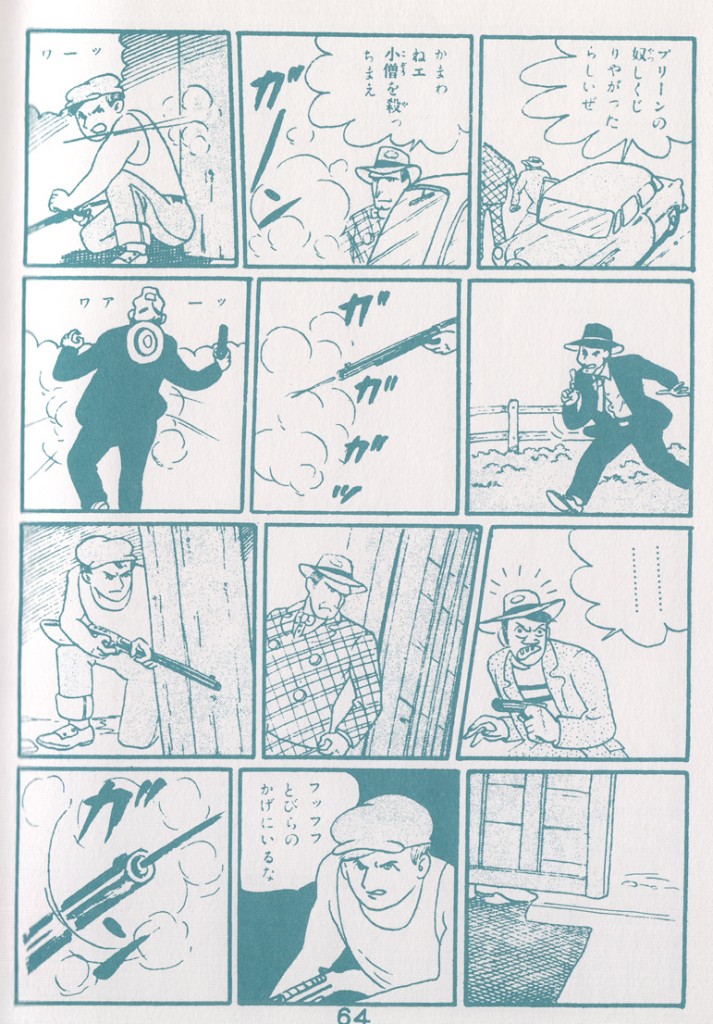

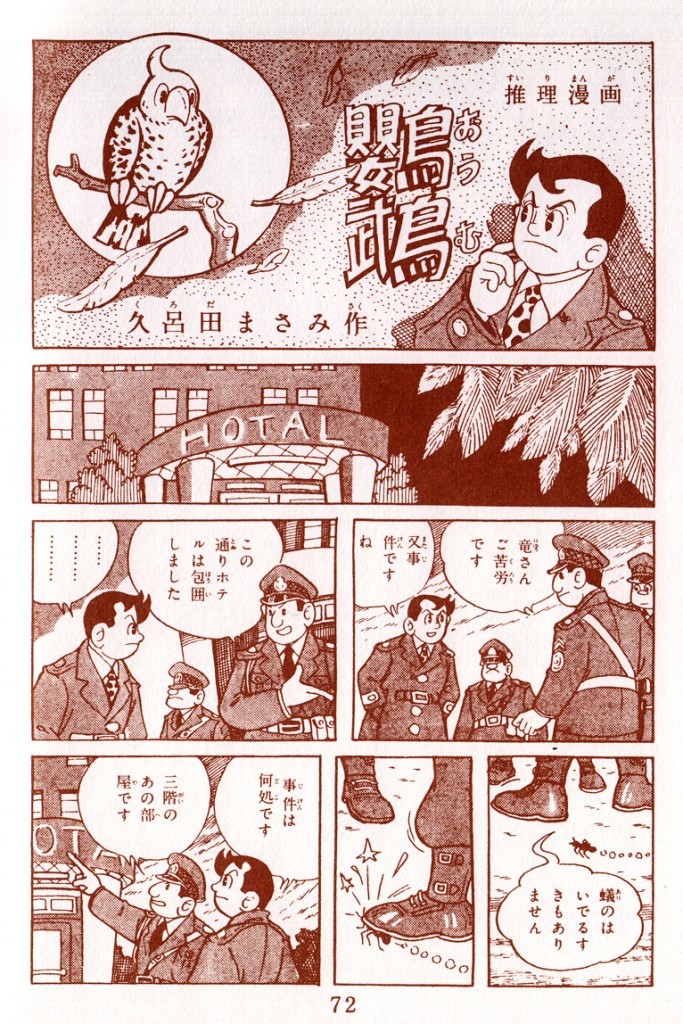

In the Japanese section, after exploring Osamu Tezuka’s breakthrough work of the late 40s and early 50s, we move on to the 1950s gekiga movement:

By 1956 or so, a small rebellion against Tezukian hegemony was stirring in Osaka,

led by a group of young up-and-comers including Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Takao Saito¯

and Masahiko Matsumoto. Reverent admirers of Tezuka, they nonetheless felt

the need for more bite in their manga, and hence gekiga (meaning “dramatic

pictures†as opposed to manga, “playful pictureâ€) was created to, as Tatsumi

put it, provide “material for those in the transitional period between childhood

and adulthood.†* Distributed through the inexpensive rental library—or

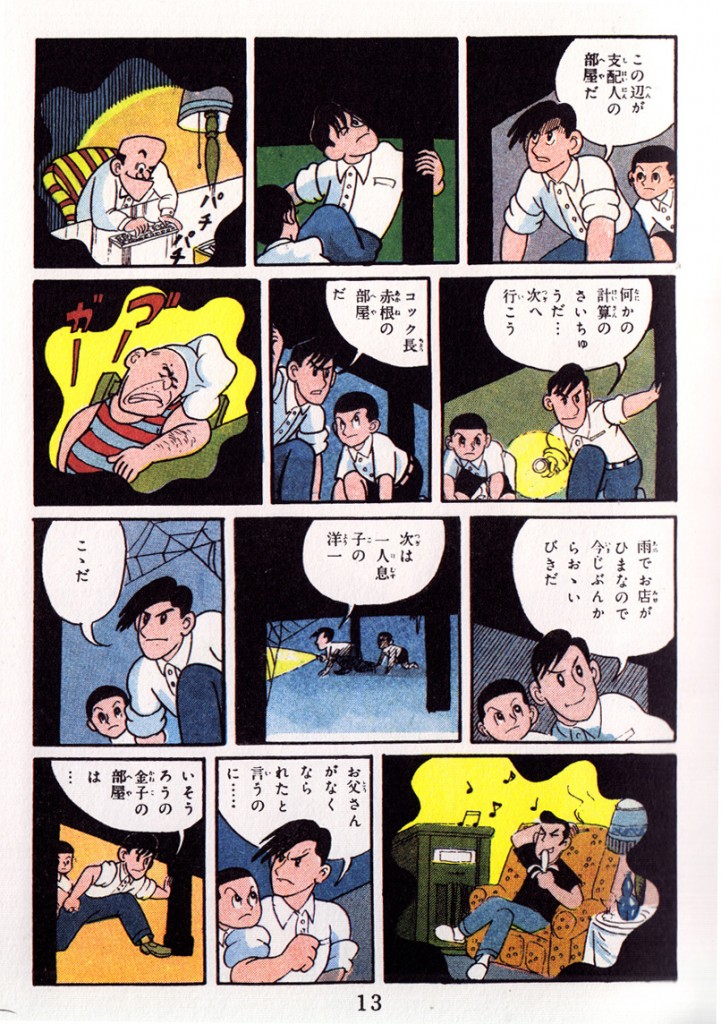

kashihon—market, the early gekiga stories were mostly thrillers and mysteries

for adolescent male readers, with cinematic paneling and lighting effects

inspired by French and American film noir.

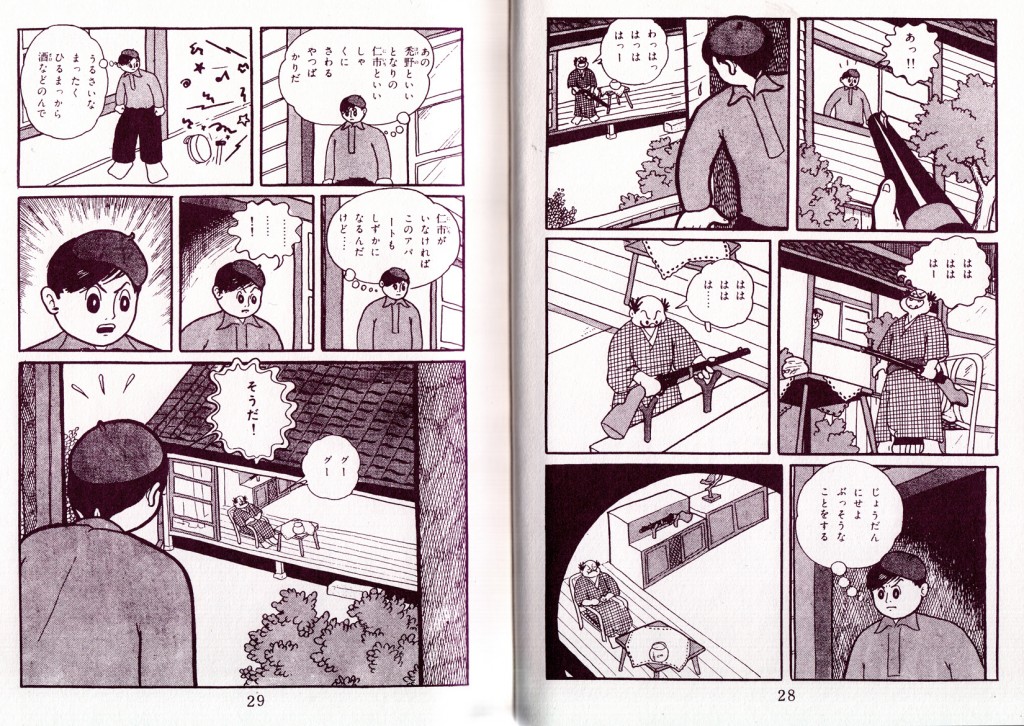

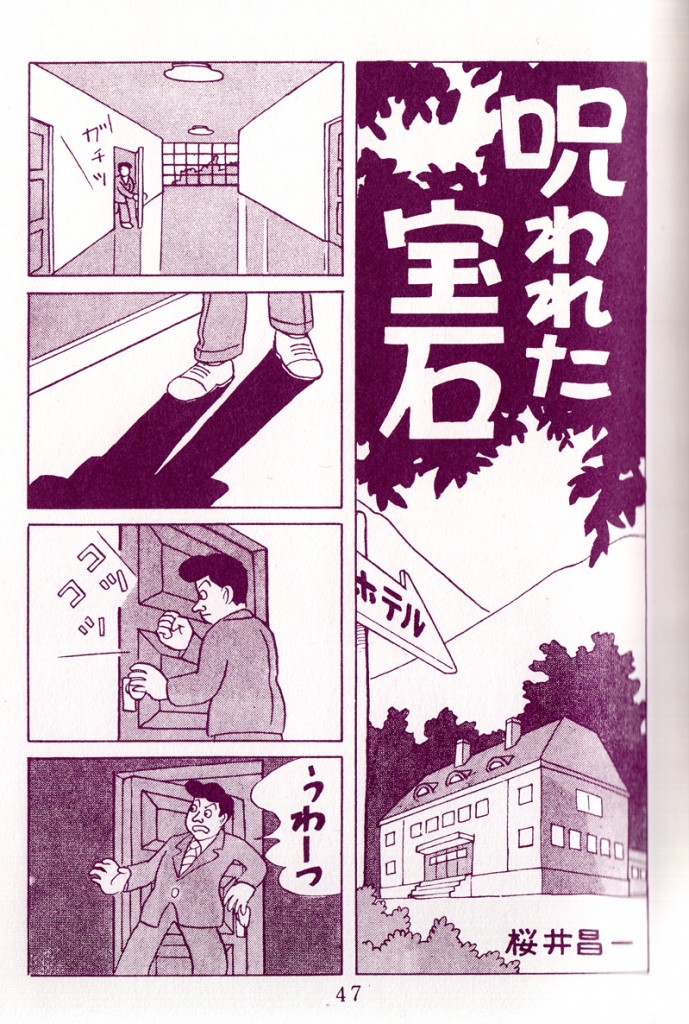

- Matsuhiko Matsumoto – Rinshitsu no otoko (The Man Next Door) – 1956 from Kage #1

The young gekiga artists of the 1950s, like Matsumoto, were great fans of Osamu Tezuka, and their cartooning style owed much to his. They pushed his “cinematicâ€Â qualities a little further, with more use of angles and of “aspect-to-aspect†paneling (images of details within a scene, employed to build atmosphere or, in the case of this page, suspense), and in general brought a darker, tougher mood to juvenile thrillers  and mysteries.

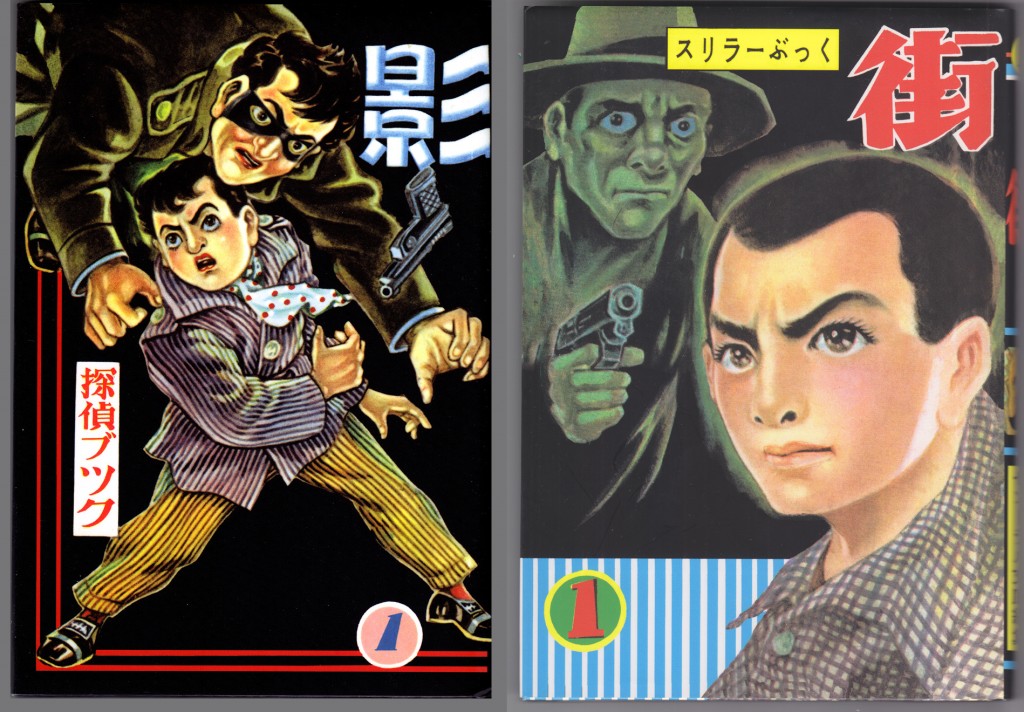

This first wave of gekiga** creators collaborated on two anthology periodicals, Kage (“Shadow”) was launched in 1956. The magazine was a success, sparking a boom in crime-themed, short story manga collections for the inexpensive kashihon market. But Kage’s small Osaka publisher, Hinomaru Bunko, was in perpetual financial straits, and when in the following year it appeared that the firm would go under, Matsumoto and Tatsumi accepted an offer from a rival to start a second, noir-ish anthology, Machi (“City”).***  Here are some images scanned from facsimile editions of the first issue of each of those titles:

*Quoted in “God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga” by Natsu Onoda Power

** The term “gekiga” wasn’t yet used during the heyday of Kage and Machi. Â Matsumoto favored the term “Komaga” to differentiate their work, geared for older readers, from manga, which was still thought of as a children’s form. Tatsumi coined the term “gekiga” a few years later.

***As recounted by Matsumoto in his autobiographical “Gekiga Fanatics”