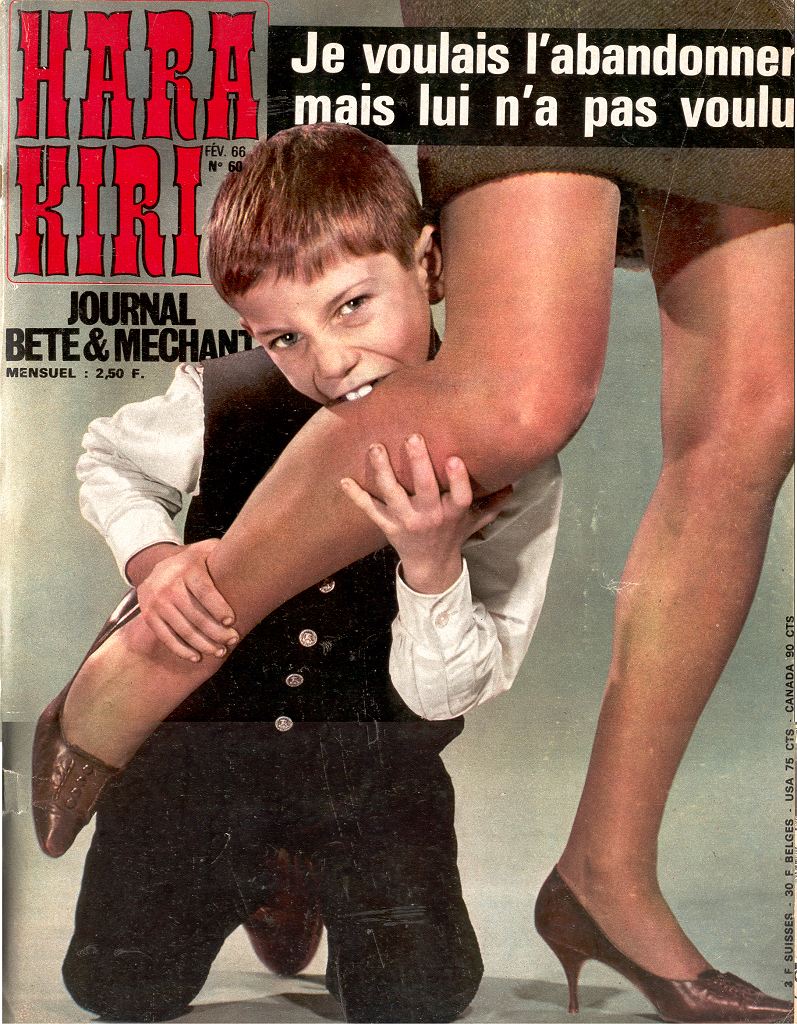

Though  not exclusively a comics magazine, the French satirical journal Hara Kiri was very important in the movement toward a bande dessinée adulte that gathered force during the 1960s.

-

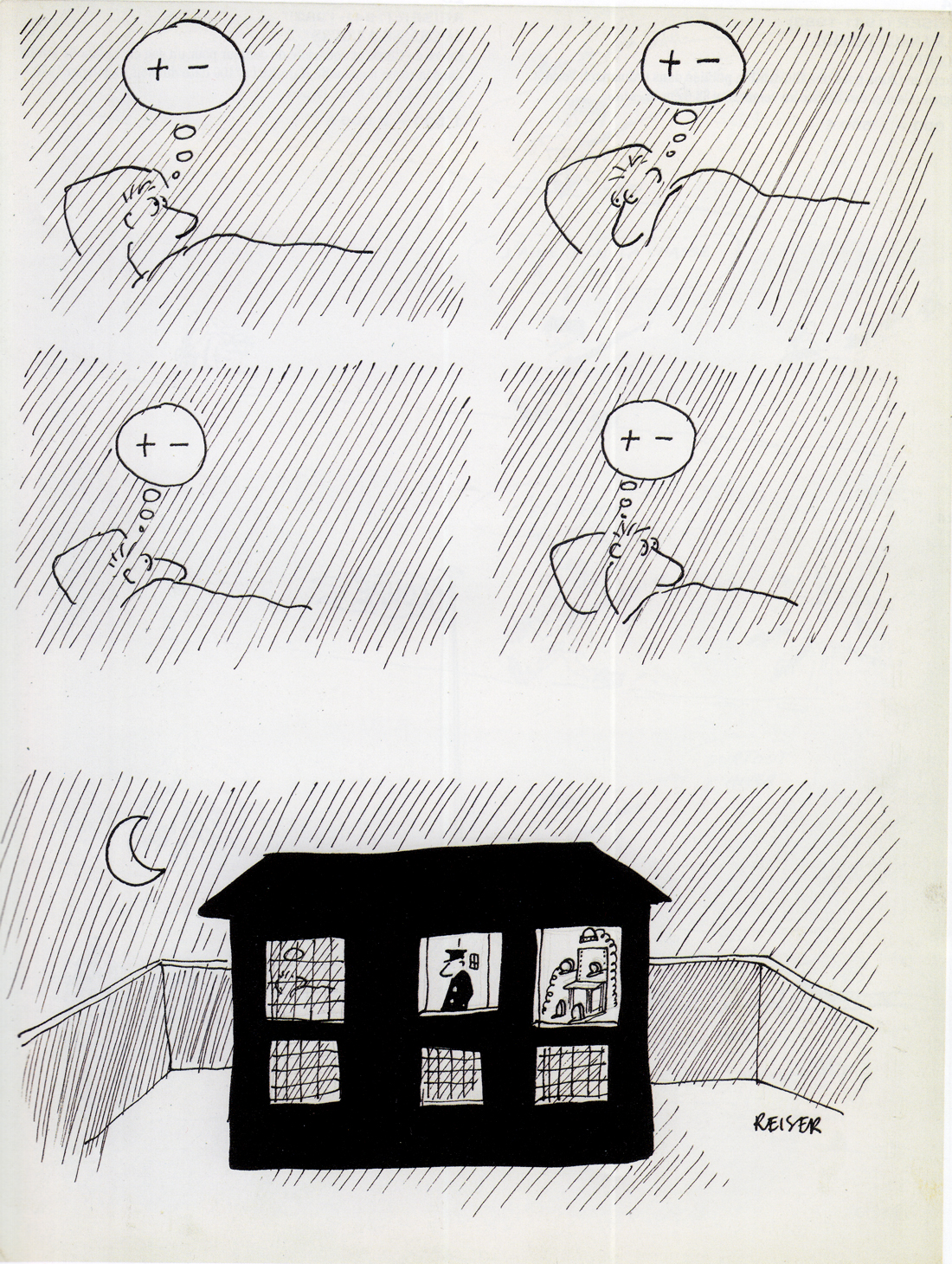

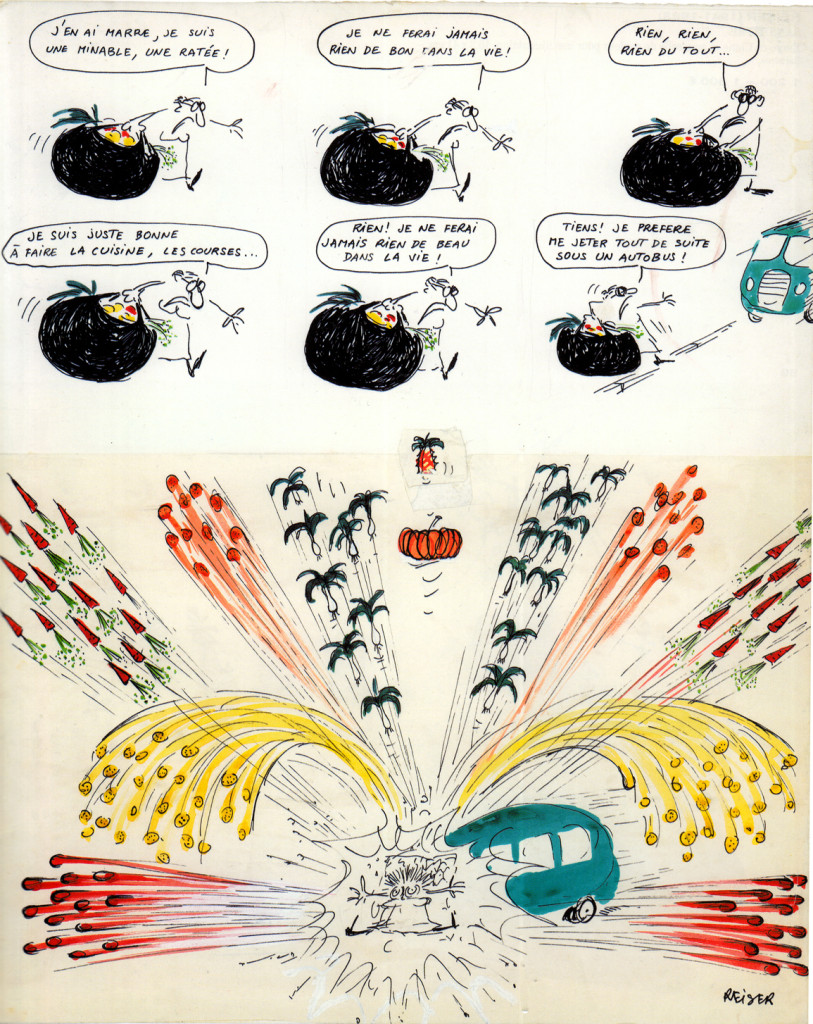

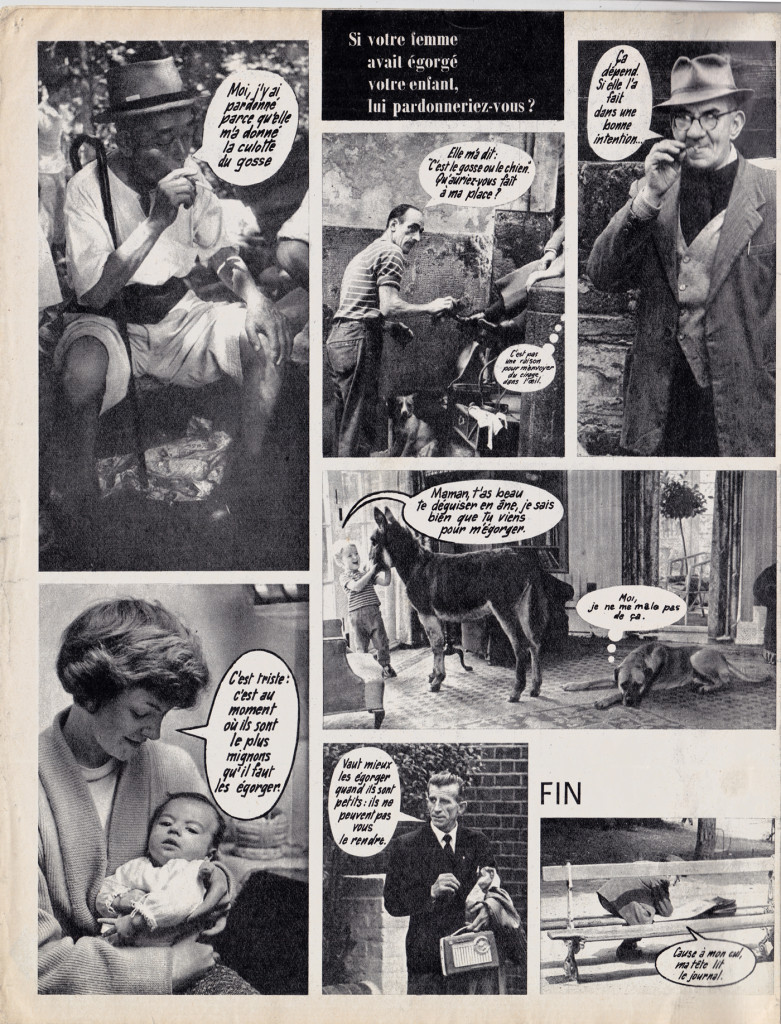

Reiser, from Hara Kiri #62, 1966. An early Reiser gag, still relatively restrained but displaying the characterisically morbid Hara Kiri humor.

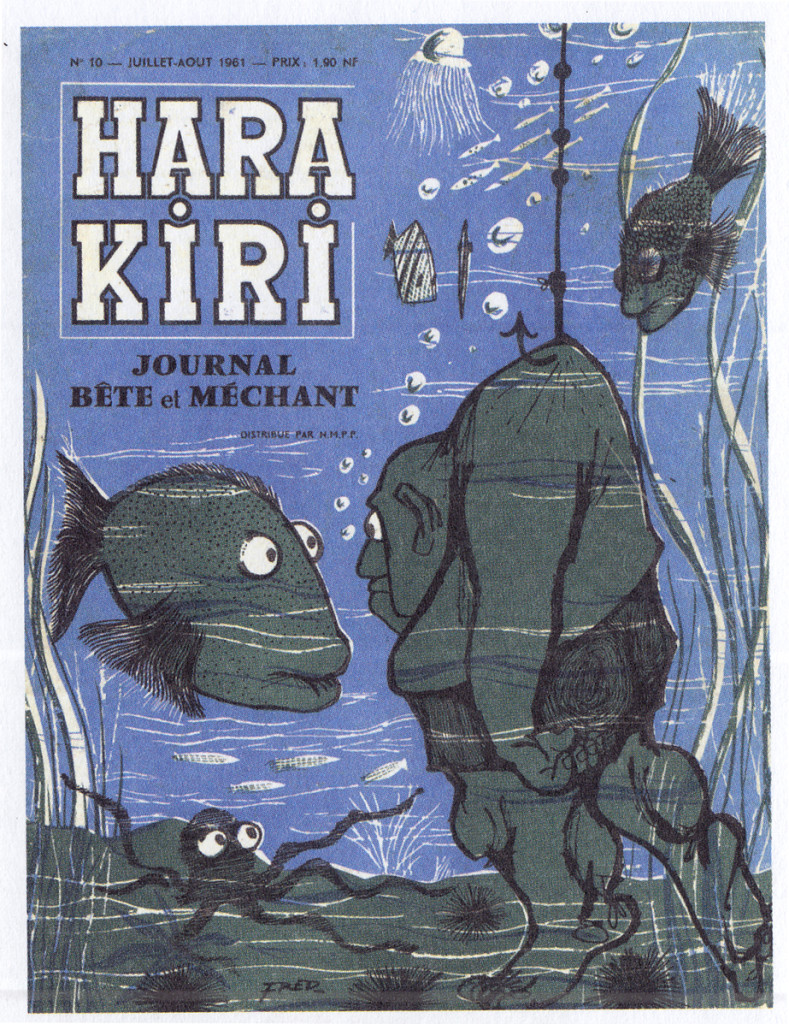

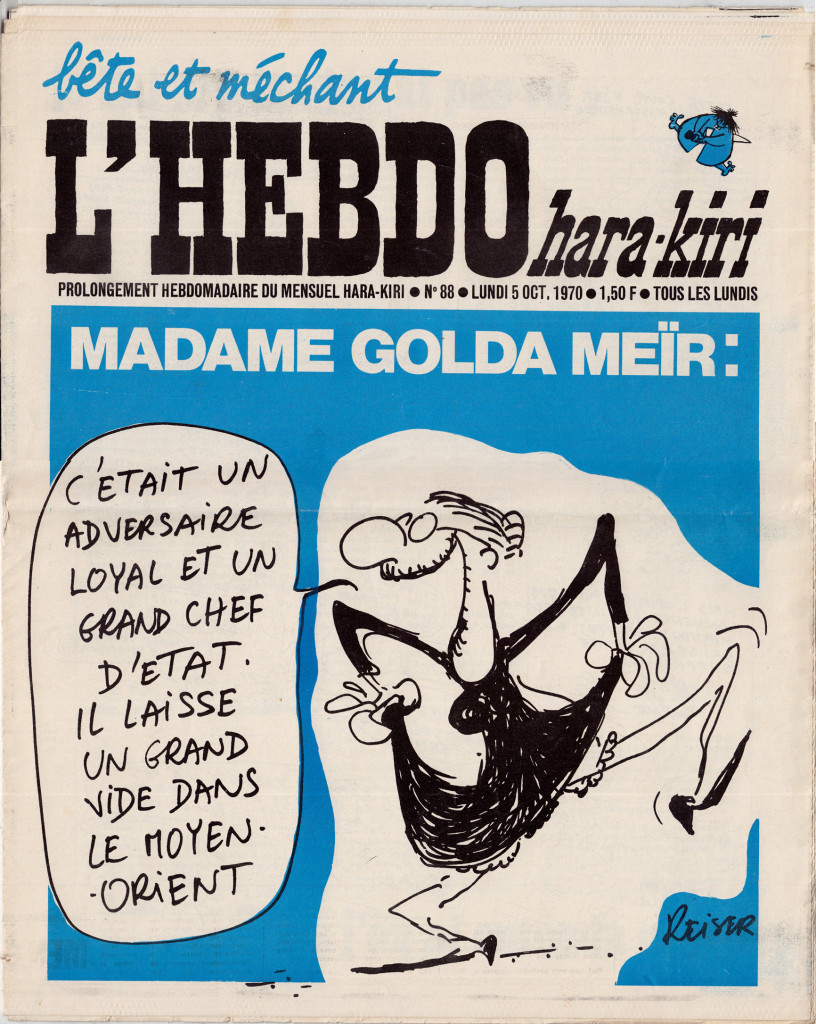

Hara Kiri, which billed itself proudly as “le Journal Bête et Méchant’ (stupid and nasty)  was founded in 1960, originally hawked on the street corners of the Latin Quarter*. Founders Francois Cavanna and George Bernier soon demonstrated a propensity for sick, shocking humor, which resulted in the magazine being banned several times.

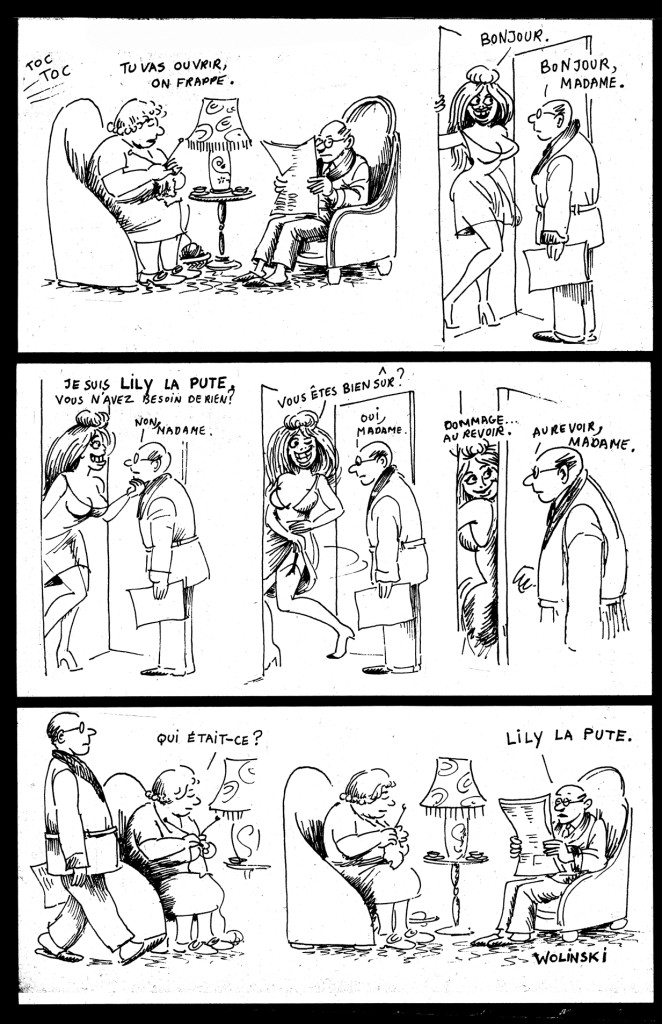

1: Open the door, someone’s knocking.

2: Hello. / Hello, madame.

3: I am Lily the Whore. Do you need anything? / No, madame.

4: Are you sure? / Yes, madame.

5: Too bad… goodbye. / Goodbye, madame.

6: Who was it?

7: Lily the Whore.

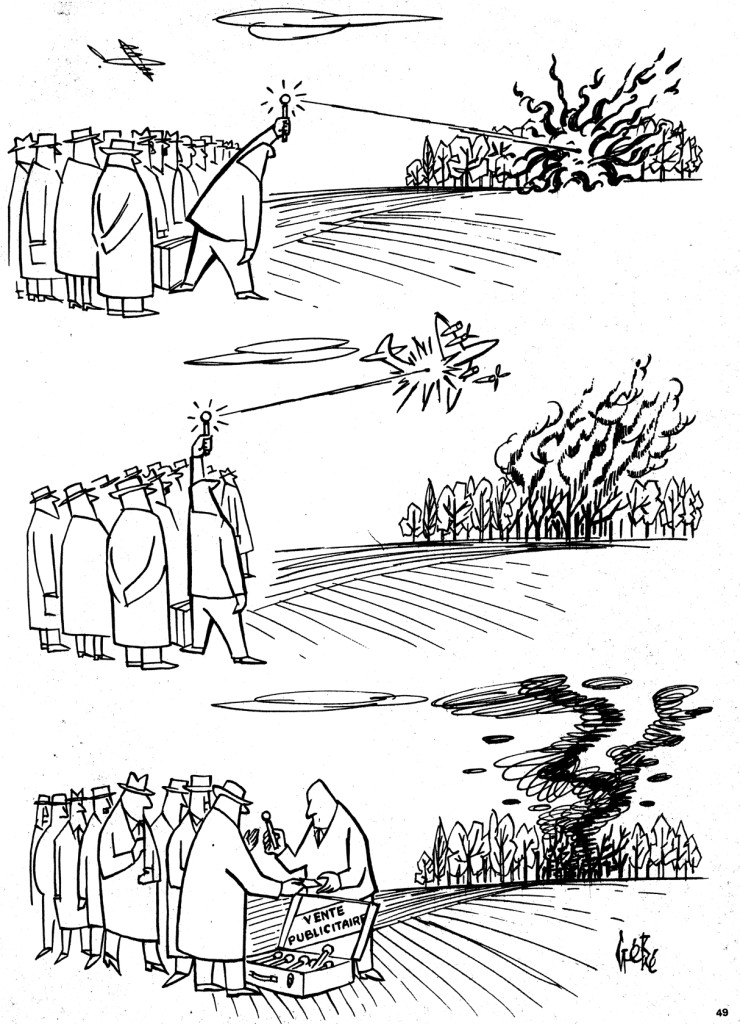

While MAD Magazine was certainly an influence on Hara Kiri, its brand of satire was far less innocent, and aimed at older readers (a better comparison in terms of format and content would be National Lampoon, which appeared in 1970).  The comics in Hara Kiri were raunchy, political, dark and decidedly adult.  In spirit, the magazine might be compared to the early underground newspapers in the U.S., like the “East Village Other” and “Berkeley Barb,” but France’s cultural climate was different — there wasn’t the same sort of burgeoning youth counter-culture economy that could generate a true underground press– so French mainstream culture had to absorb the full,  bête et méchant brunt.

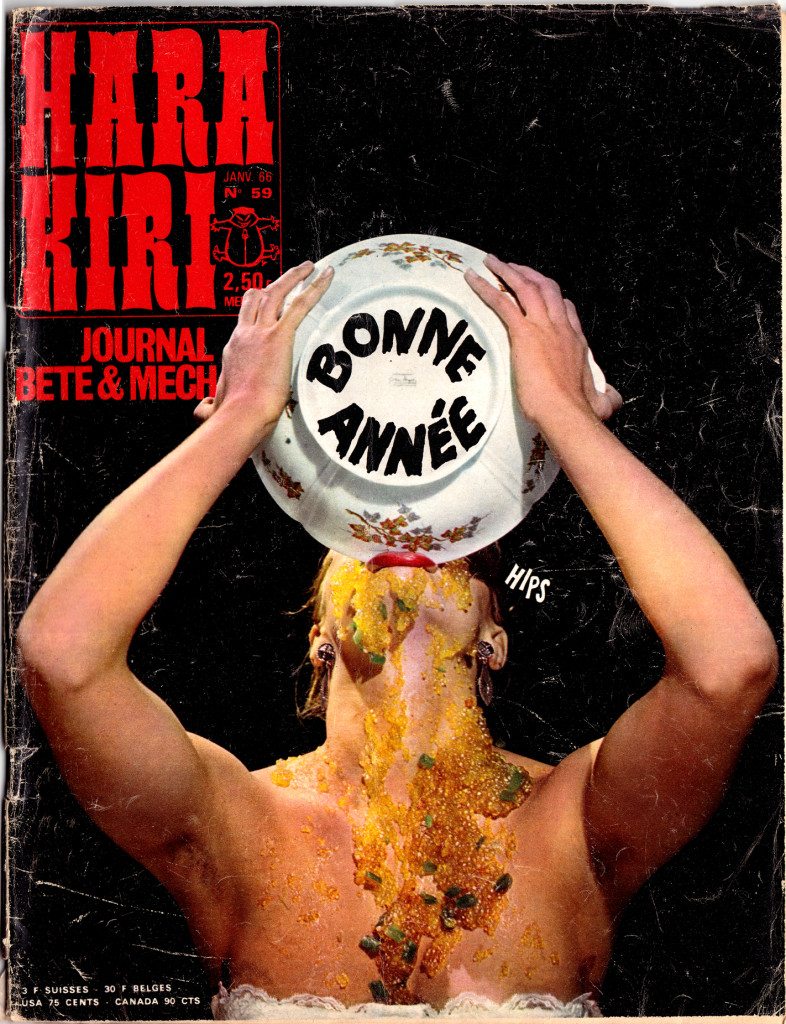

Early covers featured illustrations, but these were soon replaced by infamous staged photographs that demonstrated the magazine’s sensibility: gross-out humor and political/social satire, often completely sexist (you’ll have to google it yourself to see the worst ones).

1: I’m fed up, I’m a loser, a nothing.

2: I’m not good for anything in this life.

3. Nothing, nothing, nothing at all

4. I’m only good for cooking, buying the groceries…

5. Nothing! I never make anything of beauty in life!

6. Dammit! I’d rather throw myself in front of a bus!

Â

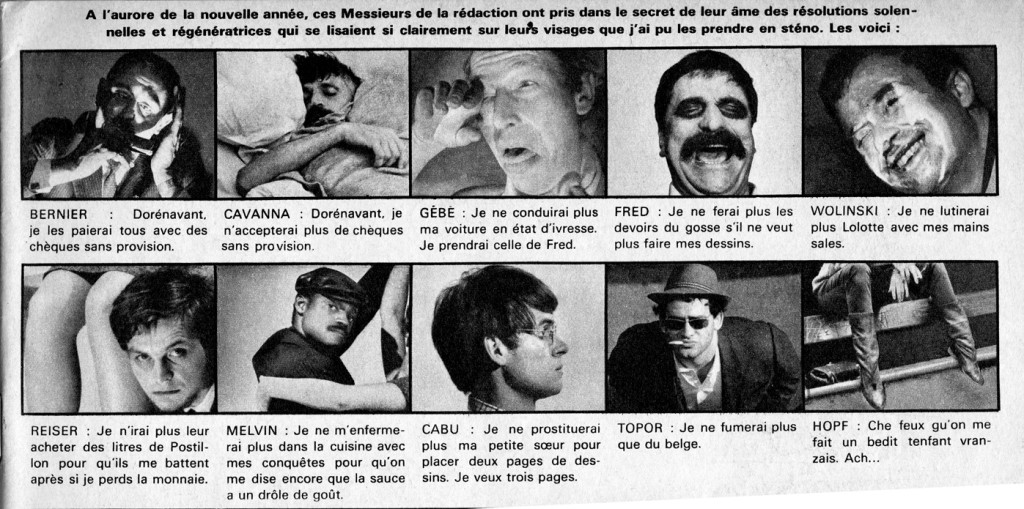

The magazine featured articles and photo-romans (photo-funnies), and  some brilliant cartooning, by a stable of artists that included Wolinski, Reiser, Gébé, Fred, Topor and Cabu (there was, I believe, a law that Francophone cartoonists were entitled to only one name apiece).

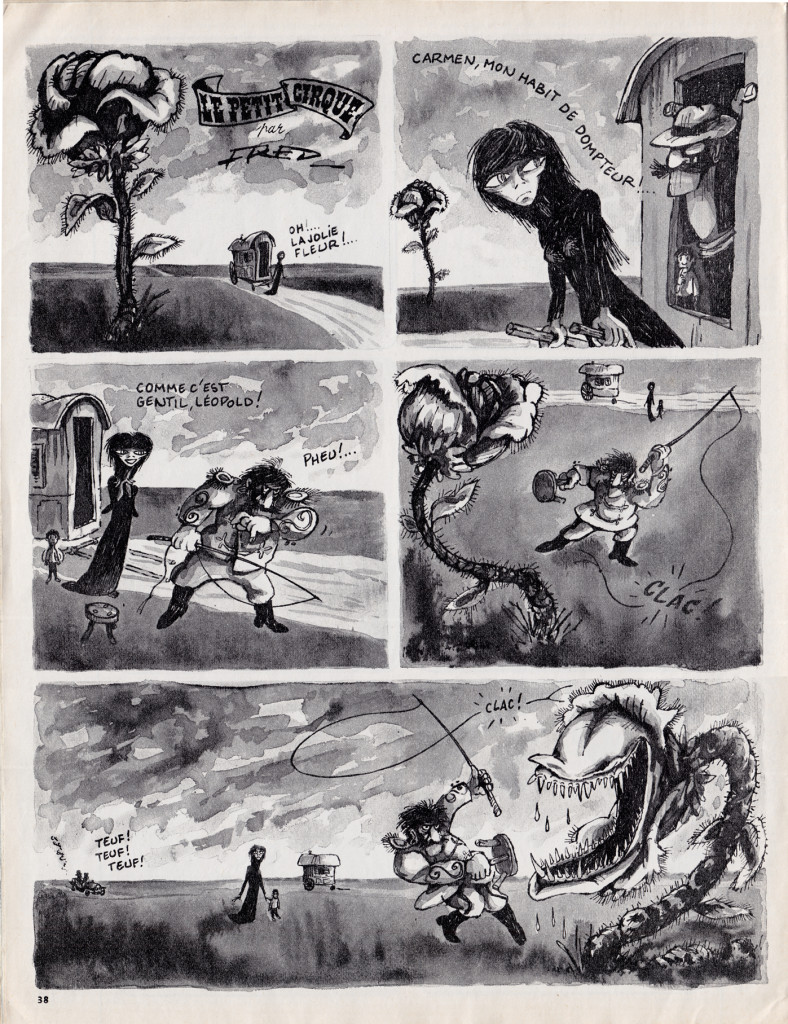

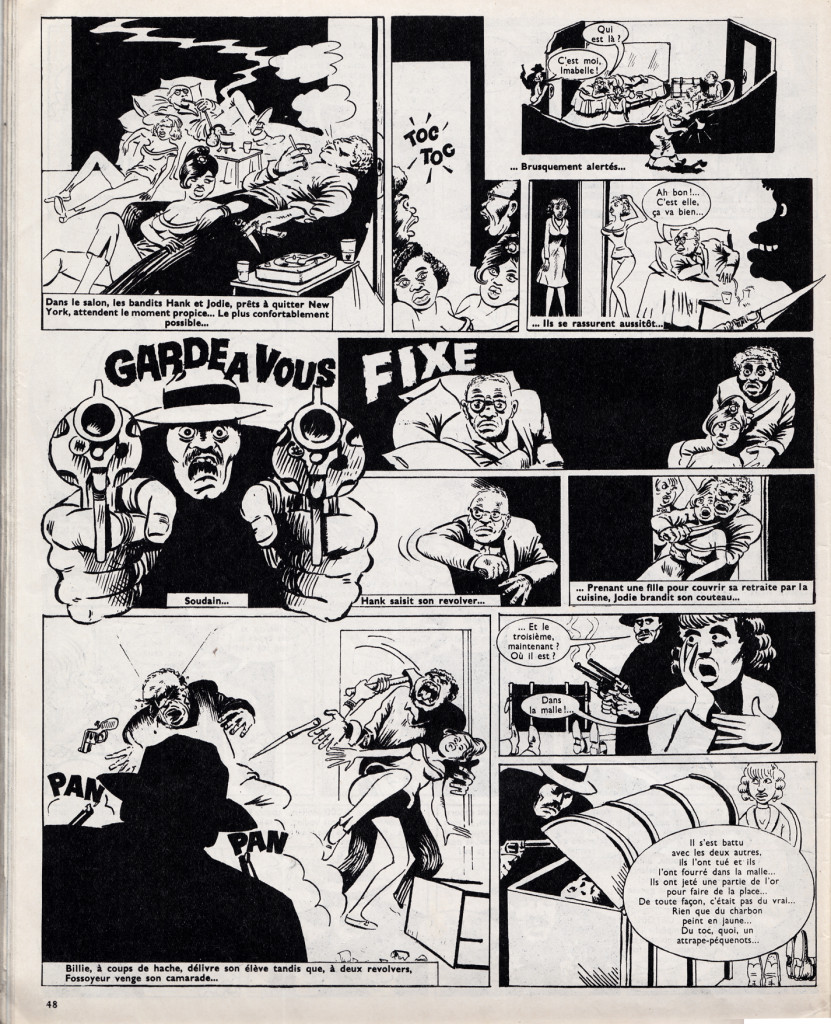

Most of the bd  in Hara Kiri were panel gags and short humor strips, but there were some important longer series as well, such as Fred’s Le Petit Cirque, Guy Peellaert’s Pravda, and a little-known but fascinating collaboration, in which American expatriate writer Melvin Van Peebles collaborated with cartoonist Wolinski to adapt the Chester Himes crime novel, “A Rage in Harlem” (known in French as La Reine des pommes)

By the early 70s, Hara Kiri had been shut down by censors often enough (most notoriously for a headline that mocked the death of Charles DeGaulle), that the magazine’s cartoonists sought greater security, first by a short-lived emigration to the pages of Pilote (only Fred became a mainstay there, with his glorious strip Philémon), and then by starting a new publication, Charlie Mensuel, devoted entirely to comics.  Charlie would represent another major support for grown-up bande dessinee for the next 20 years.

* Thierry Groensteen, La bande dessinée, son histoire et ses maitres, Skira Flammarion, 2009